TEMPLE HERITAGE

Scattered throughout the mountains and plains of central and eastern Java are the remains of numerous stone temples dating roughly from between the eighth and fifteenth centuries. Taken together, they tell story of the rise, development and decline of Java’s Hindu/Buddhist civilization.

Generally speaking, the Central Javanese monuments are earlier than those found in the eastern part of the island. Most were built between about 750 and 950 A.D. Exceptions are the curious structures on Mt Lawu near Solo, which date from the 15th century, right at the end of the Hindu/Buddhist period.

The temples of Central Java were the work of master builders, who drew their inpiration from Idian architectural models. The principals upon which they built, however, are far older than either Hinduism or Buddhism and are rather connected with the ancient belief that humans are somehow influenced by subtle forces emanating from stars, planets and from the cardinal directions. Aside from functioning as places and of worship, then, these sacred buildings were magical diagrams representing the order of things in the unseen world. The groundplans were invariably symmetrical and carefully aligned with the points of the compass, entrances usually facing eat or west, towards the rising or setting sun. In the case of a large complex, like Prambanan, minor buildings were balanced around a tall central structure. The focus was towards the center, the direction vertical, to the heavens. In short, Javanese temples were earthly replicas of the spiritual mansions; places where gods and ancestral spirit would be inclined to congregate, feel at home and, hopefully, mingle with humans.

Temples also sometimes functioned as shrines for departed leaders, a tradition harking back to the times of primitive ancestor cults. Following the death of a powerful ruler, a funerary statue of the monarch as a god or potential Buddha would be created and a temple built to house the image. The Indonesian term cand, meaning ‘ancient shrine’, is nowdays used to indicated all manner of sacred sites, including bathing pools or even rocks. Principal temples in Central Java include those on the Dieng Plateau, the Gedong Songo group on Mt Ungaran, Candi Sukuh and Ceto on Mt Lawu, as well as the famous monuments or Borobudur and Prambanan near Yogyakarta. The best times to visit these places is in the early mornings or late afternoons when the weather is cooler, the light better for photography, and in the mountains the visibility more likely to be clear. In fact, the optimum time for photographing these beautiful objects is immediately following the rain, when the vegetation surrounding the temples appears green and fresh, and the stone glistens.

Principal Temple Sites – Yogyakarta and Central Java

| Vicinity | Temple | Date |

| Yogyakarta | Prambanan | Hindu, Mid 9th C. |

| | Sewu | Buddhist, Late 8th C. |

| | Plaosan | Buddhist, Early 9th C. |

| | Kalasan | Buddhist, Late 8th C. |

| | Sari | Buddhist, Early 9th C. |

| | Sambisari | Hindu, 9th C. |

| | Sojiwan | Buddhist, Early 9th C. |

| | Ratu Boko | Hindu/Buddhist, 8th-9th C. |

| Magelang | Borobudur | Buddhist, 8th-9th C. |

| | Mendut | Buddhist, Early 9th C. |

| | Pawon | Buddhist, Early 9th C. |

| | Gunung Wukir | Hindu, Mid 8th C. |

| | Ngawen | Buddhist, Early 9th C. |

| | Selogriyo | Hindu, 9th C. |

| Parakan | Pringapus | Hindu, Mid 9th C. |

| Wonosobo | Dieng Temples | Hindu, 8th – 9th C. |

| Ungaran | Gedong Songo | Hindu, 8th – 9th C. |

| Tawangmangu | Sukuh, Ceto | Hindu, 15th C. |

The Temple of Prambanan

While scholars may be uncertain as to who built the temple of Loro Jonggrang at Prambanan, there is no doubt in the minds of local residents that it was constructed in one night by Bandung Bondowoso. The legend surrounding the temple goes something like this :

Loro Jonggrang was the daughter of Ratu Boko, whose palace was situated on Ratu Boko Hill, to the south of Prambanan. When a dominic warrior prince by the name of Bandung agreed, on the condition that he build for her a vast temple in a single night. Undeterred by the request, Bandung Bondowoso took up the seemingly impossible challenge and, when evening came, set to work. As the result of his extraordinary magical powers, the temple began to take shape rapidly and by 3 o’clock in the morning it was almost finished. Seeing that her conditions were going to be met, and that she would be forced to marry this unwelcome suitor, Loro Jonggrang immediately ordered the villagers to begin pounding rice, which was a customary sign that the new day had begun. At that moment, Bandung Bondowoso had only one more atatue to complete. In his anger at having been tricked in this way he cursed the princess and turned her into the image of Durga which now stands in the northern chamber of the main temple at Prambanan.

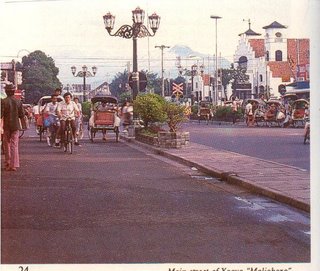

Prambanan today is a small village lying about 16kilometres east of Yogyakarta. To the north lies the smouldering mass of Mt Merapi. For the ancient Javanese who lived in it’s shadow, the mountain was a sacred symbol, the resting place of gods and ancestors. It was the great provider, source of the swift flowing rivers which poured down from it’s slopes to water the fertile plains. When angered, however, it would erup violently, causing the most awesome devastion. Little wonder, then, that it was deemed necessary to placate Merapi’s resident spirits with prayers and offerings.

The Ramayana Ballet

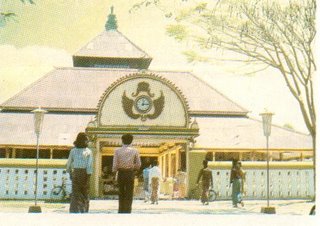

A unique event Yogyakarta is the performance of the Ramayana Ballet at the Prambanan Theatre, using the tempke as a backdrop. The balet, which involves a huge cast of more than 100 dancers and musicians, is staged on four consecutive nights around the full moon during the dry season (May – Oktober).

Other Temples in the Prambanan Region

The Loro Jonggrang temple is just one of literally scores of archaeological sites in the immediate vicinity of Prambanan. While many can only be approached on foot, most of the major temples can be covered in a few hours by andong.

Two important Buddhist temples, Sewu and Plaosan, lie a short distance from Prambanan to the north and north east respectively. Candi Sewu, which literally means ‘1000 temples’ is an enormous complex containing some 250 separate buildings arranged in a mandala pattern. Built during the late 8th century, the temple is currently undergoing reconstruction.

About a kilometre to the east of Candi Sewu stands temple o Plaosan, which should not be missed. While much of the site is in ruins, one of the main buildings has been restored and the temple displays some of the most refined sculpture to be found anywhere in Central Java. To the south, on the others side of the main Yogya-Solo road, The 9th century Buddhist temple of Sojiwan is worth a visit.

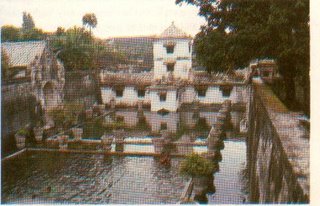

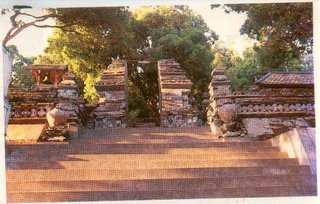

Still more remains to be seen on the Ratu Boko Hill, about two kilometres directly south of Pambanan. The principal objects of interst, which are easily accessible, are the ancient entrance gates, Pendopo Terrace and bathing pools, apparently part of what may once have been a fortified palace. This area has only recently begun to be examined seriously and it is still shrouded in mystery. For those with more time to spare, the are many more old temple sites which can be reached on foot from Ratu Boko, oncluding Candi Barong, Banyuibo, Dawangsari, Miri and, futher afield, candi Ijo.

More temples lie within a short distance of the main Yogya-Solo road on the 16 kilometre stretch between Yogyakarta and Prambanan. Candi Gebang, Sambisari, Kalasan, Sari and Moragan are all worth visiting.

Candi Gebang, a small Hindu temple which was discovered in 1936 and has since been restored, can be found 7,5 kilometres north of the main road. A left turn at the Sri Wedari Hotel, 7 kilometres from the city, lead ti the site.

Candi Sambisari, which lies 2,5 kilometres north of the main road, 12 kilometres out of town, was not discovered until 1966.A farmer working in the fields came upon some stones displaying carved decoration and reported his find to the Archaeological Service. Excavations which followed recvealed a 9th century Hindu temple lying buried nder 6 metres of volcanic dust and ash. After 20 years of restoration work. Sambisari was formally opened to the public in March 1987.

An inscription conected with Candi Kalasan is dated 778 A.D. making this temple one of the earliest ‘dated’ monuments. The remains of this impressive Buddhist structure, which displays some extremely refined decoration, are visible 50 metres to the south of the main road at the village of Kalasan.

Candi Sari is located a short distance further a long the road to the east of Kalasan, on the northern side. It is a Buddhist temple resembing Candi Plaosan in form and dates from about the same period.

Lastly, for those who are interested in seeing an excavation in progress, it is worh visiting Candi Morangan, which is still half buried underground about 2 kilometres north of Kalasan. A small signpost on the main road, easily missed, points the the way to this small Hindu temple , which has just recently been discovered.